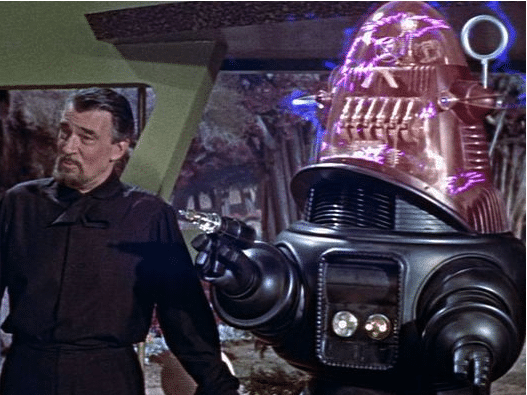

The issue has provided material for many entertaining science fiction stories. In the classic movie “Forbidden Planet,” mad scientist archetype, Dr. Morbius, demonstrates the “fail-safe” features of his creation, Robbie, by ordering it to fire a blaster at the story’s protagonist. As Robbie begins to comply, he freezes in response to a spectacularly visual short circuit. He has been designed to be literally incapable of harming life.

When legendary science fiction writer Isaac Asimov saw the film, he was delighted to observe that Robbie’s behavior appeared to be constrained by Asimov’s own Three Laws of Robotics which he had first expressed a decade earlier.

Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics can be summarized as follows:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given to it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

In Hollywood, such a benign view of the issue is somewhat the exception as AIs like the malevolently psychotic HAL in “2001: A Space Odyssey” or the terrifying robot berserker in the Terminator series make for more visceral thrillers.

“Forbidden Planet” was released in 1956, the same year as the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, a summer workshop widely considered to be the founding event of artificial intelligence as a field. Optimism that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it” was very high. Visions of robots like Robbie with powerful intellects, capable of independent action and judgment, seemed completely achievable.

But it has turned out to be harder than it appeared. Six decades later such powerful AIs still do not exist. Along the way, the field has been prone to cycles of optimism and pessimism, and researchers found it necessary to coin new terms. “Narrow AI” describes what researchers are working on at any given time, with AIs like the fictional Robbie, which was the original goal of the field, referred to as “Artificial General Intelligence.”

AI safety contains two very distinct sets of considerations depending on whether we are talking about narrow or general AI. Safety, in the narrow context, is concerned with the prudent and ethical use of a specific technology which, while it may be quite complex, is essentially the same as with any powerful technology, for example, nuclear power.

All these considerations also apply to AGI, but there is a critical additional dimension: how do we ensure it won’t be them that is deciding how to use us since they are potentially more powerful and intelligent?

Over the last decade, AI safety and ethics have become important societal concerns as machine learning algorithms have come into widespread use, collecting and exploiting behavior patterns and preferences of Internet users and generating “bots” to propagate mis/misinformation. The dangers and safety issues are, in some cases, harmful unintended consequences, while in other cases the bad behavior is intentional. But this is narrow AI, and in all cases, the issues are not about AIs misbehaving, since narrow AI doesn’t have any choice about how it behaves, but about the choices people make when training and applying it to certain practices.

Today the distinction between using narrow AI in a safe and responsible way, and the imagined dangers of future AGIs, are becoming conflated in the public debate. When OpenAI released ChatGPT, a chatbot based on the GPT-3 large language model (LLM) last November, people were stunned to discover it could generate text, even whole documents, that appeared to articulate concepts and communicate ideas like humans do.

While the experts, including the developers of LLMs, point out that chatbots are not actually communicating (they have no comprehension of what the text they generate means to humans and no internal concepts or ideas to convey in the first place), the illusion of intelligence is so seductive to human psychology that few can resist the impression that a mind exists inside ChatGPT and others.

This has led to a widespread belief that AI technology is advancing at a rapid pace and that true AGIs must be just around the corner; thus, the widely recognized shortcomings and dangerous side-effects of current AIs are seen as a step toward the darker and more serious existential dangers that are imagined from AGI.

While fear of dangerous AGI has been around as long as science fiction, it was first articulated as a practical concern in Ray Kurzweil’s book, The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, published in 2005. Kurzweil speculates that all information technology advances along a logarithmic curve driven by Moore’s law and therefore real AI, general intelligence, can only be decades away.

Kurzweil does not stop there. The book embraces the concept of the Singularity popularized by science fiction writer Vernor Vinge in his 1993 essay, “The Coming Technological Singularity.” The idea is that if we can build AIs as intelligent as we are, then we can build ones that are more intelligent than we are, and those AIs can do the same, and so on and so on without end. Thus, a curve representing intelligence in the world increases asymptotically: a singularity.

0 Comments